A Case for Compassion: The Movement Against Solitary Confinement

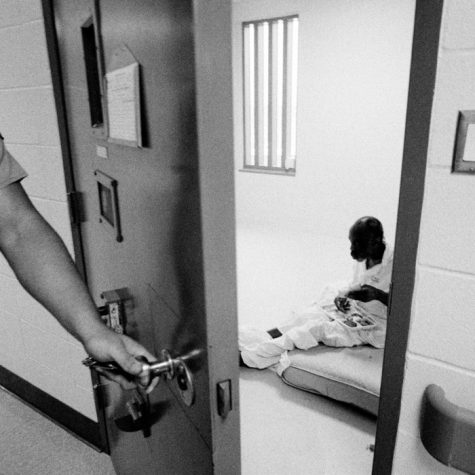

Around 80,000 people in the United States are currently trapped in a room no larger than 10 feet long. For reference, that’s only a little bit larger than Oakton’s bathroom stalls. Many of them haven’t seen another person in hours, even days. The lights in their room glare against their plainly colored furniture through the night, making it difficult for them to sleep. They have no access to outside resources, like books, TVs, or games. Their days consist of staring at blank walls, questioning and re-questioning their own humanity.

This is the reality of the American prison system, in which solitary confinement is leveraged as a punishing resource for misbehavior. The “tool” emerged years ago following its use as a war tactic and has since existed as a means of preventing internal prison violence. However, recently the practice has received heightened levels of national scrutiny, prompting many human rights advocates to question whether the form of psychological (and often physical) violence that the practice creates is truly an effective means of ensuring prisoner safety.

Solitary confinement is most often used as a punishment for prion fights and threats. Though it has been proven to be an effective deterrent in some cases, the rise of prison violence in places that practice solitary confinement exists in glaring contrast to the continually-emphasized promises of “decreased violence” that the practice is supposed to encourage. For example, a 2017 study found that prisons that decreased their use of solitary confinement saw a complementary decrease in violence.

Additionally, the issue of solitary confinement poses problems in the way and means by which it is delegated to prisoners. Minorities and prisoners with mental illnesses are most often the ones that face solitary confinement, and frequently face it for less violent altercations than their white or able-bodied peers. This often occurs because prison guards hold the responsibility of delegating punishment within the walls of prisons, meaning that prisoners can stay in solitary confinement for days before outside opinions are considered. Particularly in more conservative states, this means that prisoners can face unofficial juries that lack the legal tools to combat intolerance that is present in more formal court procedures.

Solitary confinement as a punishment is ultimately ineffective because of the mental tolls that it takes on prisoners. “Many prisoners become so desperate and despondent that they engage in self-mutilation,” explained Psychiatrist Chris Haney. In many cases, prisoners will hallucinate and/or develop severe mental illnesses. This is primarily a result of the severe isolation, and the basic human necessity of stimulation, whether through conversation with others or with the outside world.

The United States prison system is no stranger to controversy over its practices, but the continued use of solitary confinement and its popularity pose a large question to the future of ethical imprisonment. In the face of increasing calls for “humane” prison reform, solitary confinement too represents a polarizing but necessary area for reform.