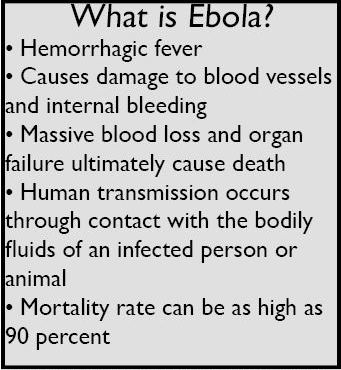

In the past few weeks, the West African Ebola outbreak has continued to threaten global health. The virus is now seen by many Americans as a major concern after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed on Sept. 30 that Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian, became sick with Ebola after arriving in Dallas on Sept. 20. Duncan was hospitalized on Sept. 28 and died a week later on Oct. 8. Since then, two nurses involved in his care have tested positive for Ebola, one of whom later flew to Cleveland, Ohio and returned by plane to Dallas afterward. Another health worker who left Dallas on a cruise after contact with Duncan is suspected of being infected as well. The CDC is tracking passengers of the nurse’s two planes and is monitoring about 50 people who have interacted with Duncan for signs of the virus, which can be spread only through contact with contaminated surfaces or blood and other bodily fluids of an infected person.

Currently, it is believed that Ebola cannot be contracted through water, food, or air, although the virus can be transmitted by infected saliva in the air from speaking. Ebola’s incubation period is two to twenty-one days, and victims become contagious as soon as they begin to show symptoms. This length of time allows the virus to be transported over far distances before an infected person becomes too sick to travel. Additionally, infected people could theoretically travel from West Africa to another country and then to the United States, and their travel history would not show that they came from West Africa first. This loophole exposes an easy way for Ebola victims to reach the U.S. and spread the virus here.

The present outbreak of Ebola in West Africa is the largest the world has ever seen, with 9,915 cases and 4,555 deaths confirmed, according to the CDC. At the current rate of infection, the number of cases in West Africa could reach 1.4 million by January if current trends of exponential growth continue. The epidemic first emerged in Guinea in March 2014 and has since spread to Sierra Leone and Liberia. These three nations are among the poorest countries in Africa, where a shortage of doctors and the lack of basic infrastructure such as running water have allowed the virus to spread rapidly. Many Africans are uneducated about the disease and do not follow safety procedures. The spread of Ebola is facilitated by traditional burial rituals, which often involve close contact with the deceased. Medical personnel in many areas have little to no experience fighting the Ebola virus and do not know how to treat infected patients. In addition, many Africans believe that illness is a punishment for wrongdoing, so they are reluctant to admit cases of Ebola to health workers.

The United States has responded by providing medical and military support to the affected regions of West Africa. On Sept. 16, President Obama announced that up to 4,000 members of the U.S. military will be deployed to Senegal and Liberia to combat the virus. The U.S. will also aid the construction of 17 Ebola treatment facilities and coordinate international efforts, and according to Obama, additional screenings will be put into place, although a travel ban will not be instituted. Other countries including the United Kingdom, China, and Japan have contributed health workers or supplies as well.

Because of the deadly and highly contagious nature of the virus, health workers have been forced to take extreme precautions when treating patients with Ebola. Health workers must wear protective suits consisting of goggles, a face mask, a surgical cap, two pairs of gloves, and a surgical gown at all times to prevent contracting Ebola. All openings are sealed with tape and the entire suit is checked by a partner to ensure safety; even a microscopic tear in fabric allows virus particles to compromise a suit’s integrity. In spite of these extreme precautions, over 370 health workers in Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia have been sickened since the beginning of the Ebola outbreak. Many have been brought back to their home countries for treatment, including the United States, France, and Norway. However, even in these controlled circumstances, health workers can become infected. On Oct. 6, a Spanish nursing

assistant was diagnosed with Ebola and is currently undergoing treatment. This is the first case of Ebola contracted outside of Africa, which has raised fears of the epidemic becoming worldwide.

There are no widely-available drugs approved by the Federal Drug Administration for treatment of Ebola. Most victims that recover from the virus do so because of proper sanitation and medical attention, such as doctors lowering blood pressure. Survivors develop antibodies to the virus and can stay immune to it for up to 10 years. An experimental drug called ZMapp containing specific antibodies exists in limited quantities, but its viability is unknown. The World Health Organization has suggested that blood from Ebola survivors could be used in treatment, but there is no evidence supporting this theory. There is also no vaccine for Ebola, though two are now in development.

While health workers are making some headway, Ebola remains a formidable threat and is expected to stay active in West Africa at least into 2015. Many health experts fear that the virus could become endemic in the region, remaining active indefinitely. The traditional response to Ebola, identifying and quarantining victims, is not effective enough in urban areas, and it is unlikely that the outbreak will be controlled soon. Even if the epidemic eventually ends, it is not projected to do so for a long time.

Categories:

2014 Ebola outbreak: what you need to know

November 6, 2014

More to Discover